There are millions of bacteria living in our guts. There are millions of dead bacteria there too. And scientists are learning just how much potential the dead ones have to improve our health

This article originally appeared in BBC Science Focus Magazine by PROF TIM SPECTOR

The term ‘gut health’ pops up everywhere these days. But while phrases such as low-carb diets, low-fat diets and high-protein snacks have come and gone, gut health is more than just a fad. Unlike previous trends, the gut-health movement is backed by solid scientific evidence gained over two decades of discovery.

We’ve known that there are helpful and harmful bacteria living in our guts for a long time, but it’s only been during the last 20 years that we’ve come to realise just how important they can be. During that time, we’ve gained insights into the effects they have on our health – both physical and mental – and the influence that the foods and drinks we consume have on them.

This voyage of discovery is far from over, though, because up until now, our research has been concentrated on the bacteria that are living in our guts. But our gut microbiomes contain plenty of dead bacteria as well. And we’re only just beginning to learn about the role that dead bacteria – postbiotics – has to play.

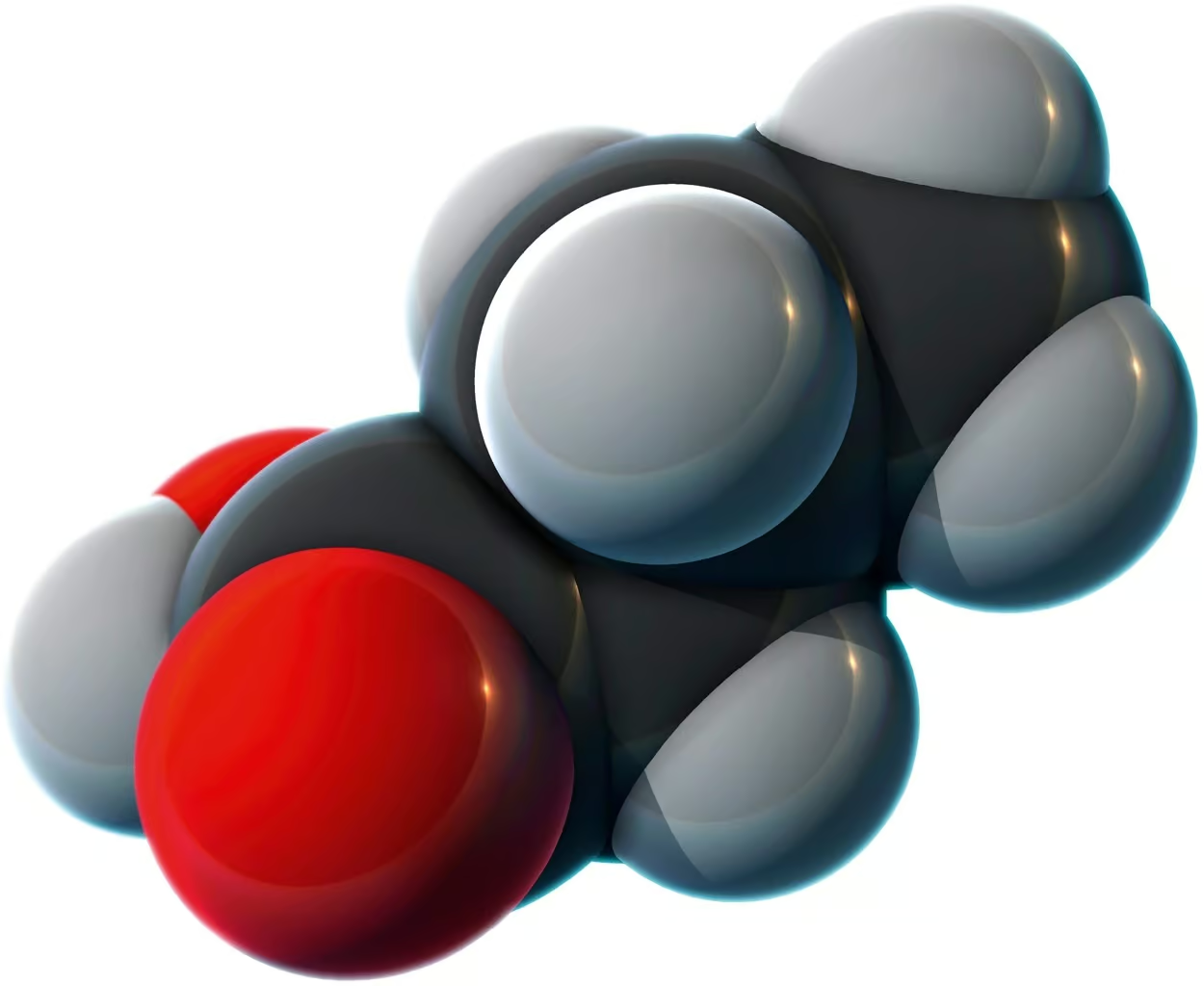

A molecular model of butyric acid, a short-chain fatty acid found in milk and butter.

SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

YOUR MICROBIOME AND YOUR HEALTH

Collectively termed the microbiome, each of us has trillions of microbes that live on and in us. We are, in short, teeming with life. Although distributed widely, most microorganisms are in our gut, specifically our large intestine – the final section of our gastrointestinal tracts, right before the exit.

Until 20 years ago, scientists believed that our gut microbiome was fairly incidental and not particularly significant for our general health. We knew that the microorganisms living in our guts helped break down some of our food, but beyond that, they were considered relatively unimportant and uninteresting.

We now know, however, that the microbes in our guts – the bacteria, fungi, viruses and more – are far more important for our health than we could have previously imagined. It’s becoming ever clearer that good gut health is good overall health.

Our microbiome evolved within us as we evolved within our environment. Since the dawn of life, this mixture of microbes and multicellular life has developed in tandem with us. It’s impossible to separate one from the other – you and your microbiome are a superorganism that’s been slowly developing together to be mutually beneficial.

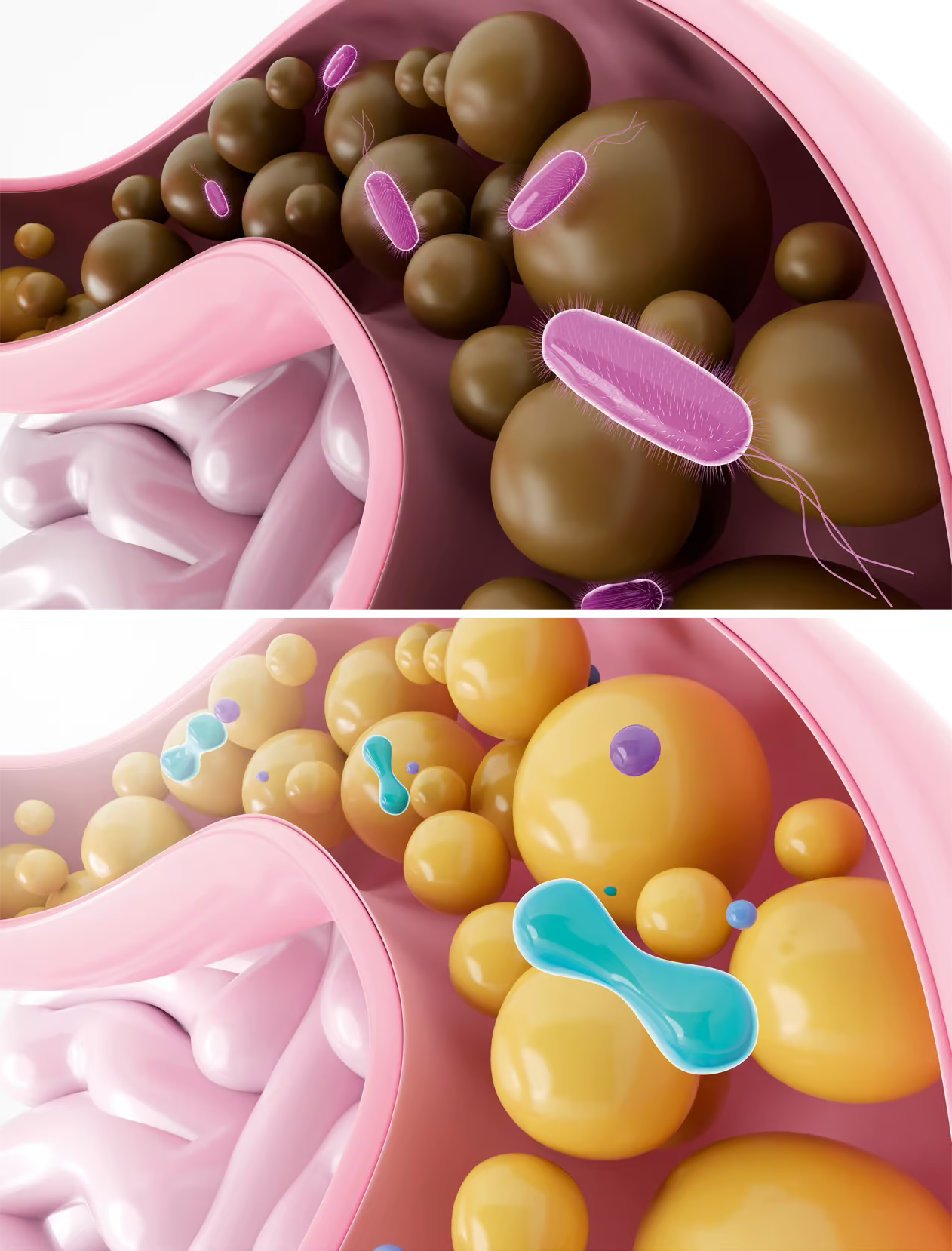

As technology has advanced, we’ve been able to dig deeper into the gut microbiome, exploring the role of individual species within it. It’s now clear that harbouring a diverse range of ‘good’ gut bacteria is associated with better overall health. Conversely, if your gut microbiome has low diversity of species and higher numbers of ‘bad’ bacteria, you’re at an increased risk of experiencing poorer health.

Recently, we’ve found associations between a disrupted gut microbiome and a wide range of health conditions, including type 2 diabetes, obesity and even neurodegenerative conditions, like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease. Whether a disrupted gut microbiome causes these health conditions or is affected by them, or both, remains an open question, but the ties between gut health and disease are now inescapable.

Kimchi, a synbiotic, contains both pre- and probiotics GETTY IMAGES

PRE- AND PROBIOTICS

As the science of the gut microbiome develops, and news of its near-miraculous importance has reached the mainstream, many of us are keen to find the most effective ways of supporting and improving our society of internal microorganisms. In this regard, the most important factor is fibre, a macronutrient that 90 per cent of people in the West are deficient in.

Previously known as ‘roughage’, doctors believed it helped ‘keep you regular’. This is certainly true, but fibre’s importance goes well beyond the frequency of your bowel movements. Fibre, present in all plants, is impervious to your digestive enzymes. This means that it makes the journey through your intestines intact, eventually reaching your colon, where the vast majority of your gut bacteria live.

Once there, fibre is fermented by gut microbes, keeping them well fed and happy. In return, gut bacteria produce a suite of bioactive compounds that support health. Each bacterium is akin to a miniature pharmacy that dispenses medicine in return for plant fibre.

One of the most well-understood microbial products of fibre fermentation are short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including propionate, butyrate and acetate. SCFAs provide energy to the cells that line your gut, helping to ensure the lining stays healthy and doesn’t leak. SCFAs also play a part in blood glucose control, reducing inflammation and more. Aside from producing SCFAs, as bacteria ferment fibre, they also produce gases and other compounds, such as indole-3-acetic acid, as well as thousands of other chemicals, including vitamins and neurotransmitters.

Bifidobacterium bifidum seen under a scanning electron micrograph.

SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

So, fibre is essential for gut health, and simply by increasing your intake you can quickly improve the health of your gut microbiome. But fibre isn’t the only way to support gut health. There are also prebiotics and probiotics.

Prebiotics, which include fibre, can be considered the soil of your gut garden, nourishing your gut bacteria. Meanwhile, probiotics are microbes that help bolster your internal community of microbes. Products that contain both pre- and probiotics are referred to as synbiotics. Fermented plant products, such as kimchi and sauerkraut, are good examples of synbiotics, because they contain fibre from the plants plus live microbes.

Although probiotic supplements are now mainstream and increasing in popularity, evidence supporting their health benefits is still lacking in most cases, especially in the prevention of disease. This is partly because they tend to contain just one or a small handful of bacterial species.

In general, the species are selected not because of their efficacy, but because it’s legal to use them and they’re easy to culture. Fermented foods, on the other hand, contain much more bacterial variety and, therefore, are much more likely to support the diversity and health of your gut’s internal ecosystem.

Different fibre from a wide range of fruits and vegetables supports a healthier, more resilient gut.

GETTY IMAGES

DEAD BACTERIA

More recently, a new -biotic has entered the scene: postbiotics. In short, postbiotics are dead microbes, parts of dead microbes, products produced by microbes or a combination of all three.

Recently, their benefits have been investigated and I’ve been surprised and excited by the results. It seems that a dead microbe still has the ability to support overall health.

How can a dead microbe impart health benefits? It’s a fair question and, I admit, I wasn’t initially convinced. It helps to imagine them like vaccines that contain inactive microbes. Although the pathogen in the vaccine is dead, the microbe still has a cell wall with proteins and triggers a response from your immune system, priming it for the next time you encounter the pathogen. In a similar way, postbiotics, despite being dead, can support your gut microbiome.

Just a few years ago, researchers would use inactivated microbes as a control in experiments. In effect, they were comparing the effectiveness of probiotics to postbiotics. After some studies unearthed surprising results from the postbiotic placebo arm of the research, scientists in Japan dug a little deeper, concluding that a heat-inactivated Lactobacillus pentosus strain could increase participants’ immune protection against the common cold.

Later research found that dead bacteria from various species were effective against a range of maladies in children, including diarrhoea and sore throats, while a large study conducted in Germany showed that dead Bifidobacterium bifidum could relieve symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). These beyond-the-grave health benefits seem almost unbelievable at first glance, but there’s now enough evidence that we can no longer ignore the ghosts of long-dead bacteria.

The study of postbiotics is still in its infancy, but I find the idea that dead or inactivated microbes can support health to be quite a relief. I always wondered whether the probiotics in sourdough might still benefit me after being baked alive, or whether sauerkraut’s microbes could still support health after being boiled in a stew. It seems that they can.

One small study, for instance, compared heat-treated sauerkraut with standard ‘live’ sauerkraut, concluding that both forms eased IBS symptoms to a similar degree.

To date, the most studied postbiotic is Akkermansia, a microbe that helps keep the barrier between our gut and bloodstream in good condition, thereby preventing toxins and other nasties from leaching into our blood. Akkermansia is associated with better metabolic health, blood glucose control and weight loss.

One of my colleagues, Patrice Cani, professor of physiology, metabolism and nutrition at the University of Louvain in Belgium and visiting professor at Imperial College London, was surprised to find that dead Akkermansia had significant anti-obesity and anti-diabetic properties in both mice and humans. Even more surprising was that the dead version was more effective than the live microbe.

Unhealthy guts (top) typically have a less varied population of bacteria.

GETTY IMAGES

THE FUTURE OF FOOD

Precisely how postbiotics can exert health benefits from beyond the grave is a topic of much scientific interest. There are likely a number of mechanisms at work, many of which may be working in unison.

One such mechanism relies on microbes’ community spirit. Fermented foods contain a wide range of species, but they don’t exist in a vacuum. They’re intimately linked, sharing food, competing for resources and protecting themselves from threats. This tight-knit community, like those found in fermented dairy, often produces rigid sugar structures known as exopolysaccharides, which serve to protect the entire ecosystem, despite being formed of highly disparate species. We could learn a lot from these cooperative lifeforms.

Research now suggests that these protective structures, rather than the microbes themselves, may help reduce inflammation and protect your gut barrier. So, even after death, the protective structures these microbes build can benefit human health. Some animal research has also shown that dried and powdered fermented foods, which contain exopolysaccharides, can reduce blood pressure and lower cholesterol. There’s even evidence that they may help protect against cancer.

Although this is a rapidly developing field, it’s becoming ever clearer that dead microbes can impart significant benefits, although precisely how will take a little more unpicking. This is clearly good news for people who cook with fermented foods, but it also opens the doors to innovation in food science.

As it stands, only a handful of microbes are allowed to be used in food products. Adding live bacteria to food is, rightfully, highly regulated. From a safety point of view, it’s important that manufacturers don’t add mysterious, unstudied species to food products and probiotics. That’s asking for trouble. It’s a similar situation for researchers: using live microbes in studies is heavily regulated for good reason. These restrictions become much less burdensome once a bacterium is deceased and can’t replicate, however.

The recent discoveries that a dead microbe may be just as useful as a live one opens the door for innovative food products and more research. Although I was sceptical initially, I now believe that postbiotics will be a mainstay in the future of functional food. Evidence is mounting that both live and dead microorganisms can support our gut and overall health, and I’m excited to see what we learn next about the wonders of microbes.

Book & Come in today to save $40 on any 60 or 75 min session. Use code: SAVE40

Save $90 – 3 session package 60 min only $327. (See details)