This article originally appeared in BBC Science Focus Magazine. By Dr. Helen Pilcher

Wait! Don’t flush! By looking at the clues in your toilet bowl, experts think you can cut the crap on what number twos say about your health.

It’s a fact of life. For those who own dogs, most know almost everything about their pooch’s poop. Every stool is inspected, bagged and then carefully binned. On any day, they can tell you if the movement was laboured, rushed, loose or firm. The same is true of the parents of newborns and toddlers.

Yet we rarely stop to think about our own bowel movements. We flush it away without so much as a farewell, but when we do this, we miss a trick. Because stools aren’t just waste – they’re an important source of information.

Forget reading the tea leaves – reading the toilet bowl can give you important information about your current and future health.

“Your gastrointestinal tract is communicating with you by giving you feedback through your stool,” says Dr Robynne Chutkan, author of the Gutbliss book and podcast, and founder of the Digestive Center for Wellness.

“This is important information that can improve your health, and maybe even save your life.”

There may be wearable tech, shop-bought kits and other devices to help monitor your wellbeing, but poop is a free resource, accessible to everyone, that provides real-time feedback on wide range of issues – if only we would give a crap about it.

Talking about stools may be butt-clenching, but for the sake of our health, we need to embrace the conversation. So, pants down, toilet seat up. Here’s what you need to know.

THE PERFECT POOP

The average poop of an adult weighs around 125g (4.4oz) – the same as half a block of butter – but this varies from person to person. The poops of vegetarians, for example, contain more fibre and water, and so can weigh twice this amount.

Faeces tend to be roughly three parts water to one part solids. The solid part contains a small amount of inorganic (non-biological) material, such as calcium and iron phosphate, and organic matter – such as undigested food, cells from the lining of the gut, and bacteria.

There are around 12.5 trillion bacteria in the average poo, of which half are still very much intact when the poop hits the porcelain.

This means that your log is alive! Bacteria account for up to half of the dry weight of a stool, including hundreds of different species, all of which hail from our guts.

Poop tests are already used in medicine. FITs (faecal immunochemical tests), for example, are used to spot early signs of bowel cancer, but as scientists learn more about how people’s stools differ, poop tests could be developed to help diagnose other conditions, such as autism and Parkinson’s disease.

Meanwhile, patients with recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection, which gets picked up in hospitals and can be deadly, are being treated with poo transplants. And yes, that is what it sounds like.

Poop from healthy donors is tested for safety, liquidised and then introduced into the guts of sick patients, via the north or south entrance. Although it may sound unsavoury, the method has a 90 per cent success rate.

These, however, are specialist procedures. We can all learn a lot from just a quick recce.

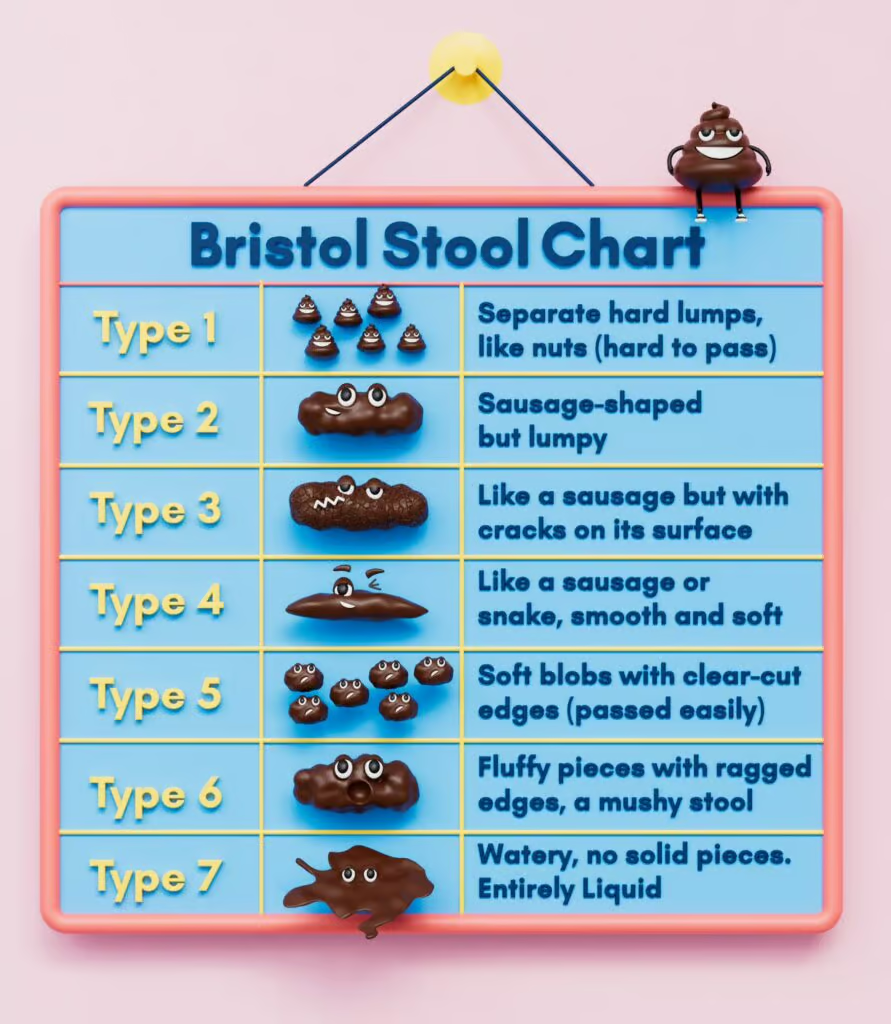

Ever since it was devised in 1997 in the city that bears its name, the Bristol Stool Chart has been used to help describe poo. It operates on a scale of one to seven, with one describing small, hard, nut-like lumps that are hard to pass, and seven describing liquid diarrhoea. In the middle – the sweet spot – a healthy dump is a three or a four, like a soft sausage that is either cracked or smooth and soft.

Stools that are too loose can be a sign of an infection or inflammation. Stools that are too hard can be a sign of dehydration.

Medical conditions, such as diabetes and thyroid disease, can alter the consistency of stools, as can dietary changes, iron supplements, food allergies, lactose intolerance and medications such as opiates and antibiotics.

But there’s more to poop than just its consistency. Chutkan recommends checking out the five C’s: consistency, colour, clarity, cut and clean-up.

Healthy stools have the hue of a milk or dark chocolate. The colour comes from bile and the breakdown of dead red blood cells. Anything other than brown, and your body could be trying to tell you something.

Green stools can be a sign of an intestinal infection, but they can also be caused by taking antibiotics.

Red stools can be a sign of haemorrhoids or bleeding in the colon (but, as you may have experienced to your horror, can also be caused by eating beetroot).

Bleeding from higher up in the digestive tract can cause black stools, but so can taking iron supplements.

Pale stools can be a sign of liver disease or not eating enough vegetables. While blue poop… we’ll get to that later.

‘Clarity’ refers to whether or not you can spot any bits of food, such as corn or lettuce. People with conditions such as Crohn’s or coeliac disease tend to have more undigested food in their faeces because the inflammation in their gut prevents nutrients from being properly absorbed. But ‘chunky bits’ can also be a sign that a person has a healthy, fibre-rich diet.

‘Cut’ relates to the poop’s proportions. A pencil-thin stool can be a sign your diet lacks fibre, or an early symptom of cancer or diverticulitis (a condition where little pouches in the wall of the large intestine become inflamed or infected). The ideal poop, says Chutkan, should be “at least the diameter of a banana, if not a plantain, and several inches long.”

And ‘clean up’ refers to any mess that’s left behind, including any odour. Do you sometimes have to avoid the bathroom after a particular family member? It’s normal for poop to smell, but when it clears a room, it’s probably a sign that the culprit has been eating a lot of sulphur-rich foods, such as meat, eggs, beans, onions and sprouts. Alternatively, intensely smelly stools can be a sign of a medical problem, such as SIBO (small intestinal bacterial overgrowth) or rotavirus infection.

According to Chutkan “stool nirvana” is a “soft, bulky stool that sends a signal when you need to go, and that exits easily, without mess.”

Everyone’s poop is different, so the key is to pay attention to yours and know what’s normal for you. Most irregularities are not indicative of a medical issue and resolve on their own, but if there is a related medical problem, there will usually be other symptoms.

“If you’re worried, don’t try and figure it out on your own,” says Chutkan. “Always consult a medical professional.”

HOW MUCH TO GO

Frequency is another important indicator of health. Most people poop once a day, but the NHS advises that it’s normal to defecate anywhere between three times a day and three times a week.

Frequency, however, has been linked to the risk of future health problems.

In one recent study, scientists tracked the bowel habits of 14,574 adults over time. Most people (50 per cent) pooed seven times a week and the most common poop was “like a sausage or snake, smooth and soft.”

Over the course of five years, differences emerged between those who pooed more or less often.

Specifically, those with soft stools who pooed just four times per week were more than twice as likely to die from cancer and heart disease than those who pooed seven times per week. They were also 1.78 times as likely to die within the same timeframe.

At first glance, it’s not easy to explain this connection, until you think about the 100 trillion or so bacteria that live in our guts, otherwise known as the gut microbiome.

In recent years, scientists have learned that as well as assisting digestion, these gut bacteria play a fundamental role in health. Our guts contain hundreds of different bacterial species. Some are good for our health. Some less so, and the composition varies from person to person.

Research by scientists at the University of Washington, in Seattle in the US, has shown that frequent pooers (who pass one to three stools per day) have a higher proportion of ‘good’ bacteria in their guts, than those who go less often.

Among these microbes are those that break down fibre to produce beneficial molecules called short-chain fatty acids. Some of these, such as butyrate and propionate, are known to have anti-inflammatory effects. This is good news because chronic inflammation has been linked to the development of many conditions, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and Alzheimer’s.

Another poo-related measure of health is transit time – the amount of time it takes for food that we eat to turn into poo. Sarah Berry, professor of nutritional sciences at King’s College London, started to think deeply about this after noticing what happened after her son ate his blue Mr Bump birthday cake.

“I remember cleaning his nappy the next day and being like Holy moly, what’s this blue poo?” she says.

An idea was born. In 2020, as part of a larger study investigating how the microbiome affects our response to food, 863 people each ate two muffins laced with blue food colouring. Then they reported when their poop turned blue.

For some, this took just 12 hours. For others it took five days. “Gut transit time varied massively,” says Berry, “and this was related to the make-up of their microbiome.”

Those with shorter transit times had healthier gut microbiomes than those with longer ones. People with longer transit times had more of the types of microbes that have previously been linked to poor heart and metabolic health. This was most pronounced for those with a transit time of 58 hours or more, who also tended to poop fewer than three times a week.

The issue here is that when poop hangs around in the gut for too long, the resident fibre-munching bacteria run out of their primary food source and start digesting proteins instead. This includes some structural proteins that are part of the gut wall, and other proteins found in the layer of mucus that protects the gut wall.

Bacteria that once were helpful start to eat the barrier that separates the contents of our guts from the rest of our bodies. The gut becomes ‘leaky’, enabling toxins and other harmful molecules to enter the bloodstream. From there, they are transported around the body, where they can trigger chronic inflammation and other potential problems.

This explains why long transit times and low frequencies are associated with an increased risk of future ill health. “We found that gut transit time is a more informative marker of gut microbiome function than traditional measures of stool consistency and frequency,” says Berry.

HOW TO GET THE PERFECT POOP

So, how best to achieve stool nirvana?

The first thing is to be aware of your bowel habits. You can do this by noticing how often you poo, and by calculating your transit time (you can make your own blue muffins but a simple serving of sweetcorn or almonds will do just as well). The sweet spot is a transit time of 14 to 38 hours, and a frequency of one to three stools per day.

Don’t just flush. Turn around and take time to assess consistency, colour, clarity, cut and clean up. And remember, you are what you excrete. So, if your stools don’t make the grade, look at your lifestyle.

“Most things like changes in colour and consistency can be solved through diet and lifestyle changes,” says Dr Emily Leeming from King’s College London, author of Genius Gut.

Exercise alters the composition of the gut microbiome and increases the abundance of good bacteria. It also makes stools easier to pass. Movement stimulates the gastrocolic reflex, which pushes food down the colon.

Water also helps to kickstart the gastrocolic reflex and keep stools smooth and supple. Chutkan recommends drinking at least half your body weight in ounces of water daily. So, a 68kg (150lb) person should be drinking at least 2 litres (70oz) of water per day.

And finally. Fibre. Fibre feeds our friendly gut bacteria and adds bulk to the stool. In the UK, the daily recommended intake for adults is 30g (1oz), but only 4 per cent of us meet this quota.

“Most of us eat about half the recommended amount,” says Leeming. “That’s a really big fibre gap that doesn’t just have consequences for going to the bathroom, but for gut health and whole-body health.”

Eat your fruit and vegetables, but make sure to also pack away beans, whole grains, nuts and seeds because these are exceptionally good sources of fibre.

The bottom line is this. If you look after your lifestyle, you look after your health, and your poop will be pristine too.

And next time you get the urge to go, remember, your poop deserves more than a cursory glance. Inspect it. Salute it. Learn from it. Give it a round of applause, and then send it on its way.

Book & Come in today to save $40 on any 60 or 75 min session. Use code: SAVE40

Save $90 – 3 session package 60 min only $327. (See details)